Understanding the significance of the 10-year Treasury is crucial for investors. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has repeatedly emphasized that the yield on the 10-year Treasury is a key focus of the administration, particularly in relation to its tariff policy.

Backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, Treasury securities are a popular investment because of their reputation for being one of the safest investments available. There are three types of Treasury securities: bonds, notes and bills, each with different maturity dates and interest rates.

• Treasury bills are short-term government bonds typically sold in durations of 4, 8, 13, 17, 26 or 52 weeks.

• Treasury notes have maturities ranging from 2 to 10 years, with interest paid every six months. Because their interest is exempt from state and local taxes, they are a popular option for investors seeking to reduce tax liability.

• Treasury bonds are long-term securities with maturities greater than 10 years, most commonly for 30 years. Interest is paid every six months.

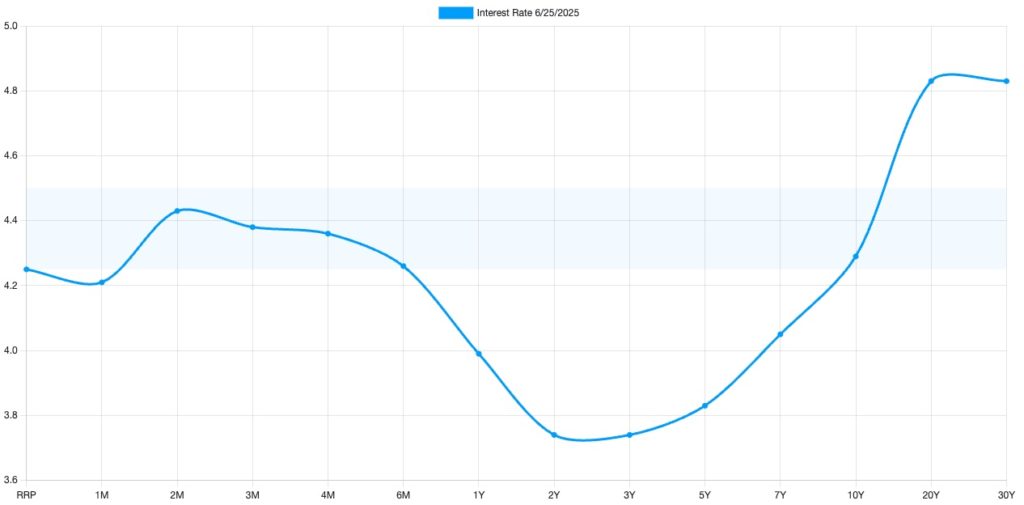

A yield curve such as the one shown below plots interest rates of bonds with equal credit quality but different maturity dates. There are three main shapes of a yield curve: normal (upward sloping), inverted (downward sloping) and flat. A normal, upward sloping yield curve is indicative of economic expansion, while an inverted curve points to economic recession.

The yield curve today is U-shaped. While short-term rates are high, they dip in the 1– to 2-year maturity range, and then increase again, ultimately creating an upward slope into maturity perpetuity. This relatively rare shape is an unusual bond market phenomenon, occurring only about 3% of the time in the past 50 years. Suggesting a complex market outlook, a U-shaped yield curve indicates a combination of near-term strength and longer-term uncertainty, demonstrated by the dip in intermediate term rates.

The left side of the chart below represents higher rates on short-term debt, such as Treasury bills. Moving along the yield curve towards longer maturities, interest rates drop, creating the bottom of the U-shape. Finally, rates rise again for long-term bonds, forming the right side of the U.

U.S. Treasury Yield Curve

What is the 10-year Treasury, and why is it so important?

A common misconception is that when the Federal Reserve raises the federal funds rate, all interest rates rise in tandem. This usually is not the case. Short-term rates are tied to the federal funds rate, while longer-term rates (such as the 10-year Treasury yield) are more influenced by the market’s outlook on growth and inflation.

The Treasury yield curve usually slopes upward, meaning longer-term securities yield more than short-term ones. This reflects the fact that investors typically demand higher yields in return for locking their money up for longer periods.

Recognized as a benchmark for the global financial system, the 10-year Treasury sheds considerable light on the current economic landscape and global market outlook. It is a bond that pays interest and returns the principal after 10 years, while its yield is the amount that the U.S. government pays to borrow money for a decade. Similarly, the yield also is the current rate that Treasury notes would pay investors if they bought them today.

The 10-year Treasury serves as an indicator of investor confidence in the economy, influencing all borrowing costs, from interest rates on bonds to mortgage rates, student loans and other forms of borrowing.

Declines in the 10-year Treasury yield generally indicate caution about global economic conditions, whereas gains signal greater economic confidence.

The 10-year Treasury also plays a role in determining the value of companies. As the 10-year moves higher, those cash flows are discounted at a larger rate — and therefore, the market value of companies is lesser in comparison.

Two primary factors affect the 10-year Treasury yield: inflation and investor perception of the economy. When the 10-year yield goes up, so do mortgage rates and other borrowing rates. Conversely, when the 10-year yield declines and mortgage rates fall, the housing market strengthens, which has a positive impact on the economy.

Higher 10-year bond yields have pushed the 30-year mortgage rates to 8% for the first time since 2000. Higher mortgage rates have hurt existing home sales, but limited housing supply haskept home prices from falling too much.

The 10-year also impacts the rate at which companies can borrow money. When the 10-year is high, as it is today, companies face more expensive borrowing costs that may reduce their ability to grow and innovate. Small businesses haven’t changed their capital spending plans yet, but obtaining financing has become more difficult, nevertheless. If businesses don’t have access to capital, that could mean less investment in the future — and fewer jobs.

The stock market also is not immune to changes in the 10-year. Rising yields may signal that investors are looking for higher return on investments, but the fear of rising rates could draw monies away from the stock market. Falling yields usually mean that borrowing rates will decline, making it easier for companies to borrow money and expand.

Lastly, global events have an impact on Treasury yields. U.S. government bonds are considered the safest investment in the world, and when there is upheaval, Treasuries are in high demand from international investors, leading to lower yields.

Why has the 10-year gone up?

The 10-year Treasury had some wild swings in the first half of the year. It bottomed out at 3.87% on April 4, surged to 4.59% a week later and eventually settled around 4.4%. Among the key factors influencing the unusual move in rates:

• Tariff announcements and retaliation are fueling concerns about higher near-term inflation.

• Investors are demanding greater compensation for owning longer-dated Treasuries with the rising debt levels and the domestic policy bill that could add trillions to the deficit.

• Foreign demand for U.S. Treasuries has softened following Moody’s downgrade of U.S. credit as well as the concern about the rising deficit.

It is likely that the Fed will slowly bring down short-term rates over the next few years. While the market expects the Fed to cut rates one or two times in the second half of this year, the Fed maintains that it will be data-dependent when it is time to reduce interest rates, remaining an independent institution not swayed by political pressure.

As we write often, it is hard to time the top or bottom of the stock or bond markets. We often don’t know that yields have peaked until long after it happens, and as we witnessed in April, we can see volatile moves in both stocks and bonds in a short period of time.

The CD Wealth Formula

We help our clients reach and maintain financial stability by following a specific plan, catered to each client.

Our focus remains on long-term investing with a strategic allocation while maintaining a tactical approach. Our decisions to make changes are calculated and well thought out, looking at where we see the economy is heading. We are not guessing or market timing. We are anticipating and moving to those areas of strength in the economy — and in the stock market.

We will continue to focus on the fact that what really matters right now is time in the market, not out of the market. That means staying the course and continuing to invest, even when the markets dip, to take advantage of potential market upturns. We continue to adhere to the tried-and-true disciplines of diversification, periodic rebalancing and looking forward, while not making investment decisions based on where we have been.

It is important to focus on the long-term goal, not on one specific data point or indicator. Long-term fundamentals are what matter. In markets and moments like these, it is essential to stick to the financial plan. Investing is about following a disciplined process over time.

Sources: Kiplinger, Investopedia, JP Morgan, Vanguard, Treasury.gov